The Death of Che Guevara

A top-secret CIA memo shows that US officials considered his execution a crucial victory—but they were mistaken in believing Che’s ideas could be buried along with his body.

About 10 years ago, I

traveled with the producers of the Hollywood film on Che

Guevara—starring the actor Benicio del Toro and directed by Steven

Soderbergh—to Miami to obtain further information for the movie about

the circumstances of Che’s execution. At a restaurant in Little Havana,

the stronghold of the anti-Castro exile community in the United States,

we met with Gustavo Villoldo, who had been the senior Cuban-American CIA

operative assigned to Bolivia in 1967 to assist in tracking down and

capturing the iconic revolutionary. Villoldo arrived carrying a thick

white binder, filled with memorabilia of Che’s execution on October 9,

1967—original photographs, secret telexes, news clips, and even the

official fingerprints taken from Che’s dead hands. The scrapbook

recorded the historic results of the CIA’s covert efforts to train and

assist the Bolivian special forces in eliminating Che and his small band

of guerrilla fighters.

In macabre detail, the retired covert agent described his

discussions with Bolivian military officers when Guevara’s body arrived,

via helicopter, from the pueblo of La Higuera, where he had been

captured and shot, to the Bolivian town of Villegrande. The Bolivians

wanted to cut off Che’s head, he said, and preserve it as proof that

Guevara was dead and gone. According to Villoldo, he convinced them

instead that they could create a “death mask” of plaster, and that

cutting off and preserving Che’s hands would be sufficient evidence.

Villoldo explained how he arranged to secretly bury the body where it

would never be found. Indeed, for 30 years Che’s remains were

“disappeared”; in July 1997, his bones, minus hands, were located in a

makeshift grave alongside an airstrip on the outskirts of Villegrande.

Fifty

years ago, US officials shared that sentiment. They considered the

capture and execution of Che Guevara as arguably the most important

victory of the United States over Cuba and Latin America’s militant left

during the era of US intervention and counterinsurgency warfare in the

1960s. Top CIA and White House officials drafted numerous secret

documents analyzing the significance of Che’s demise—for Fidel Castro

and Cuba, and for US interests in blocking the spread of revolution in

Latin America.

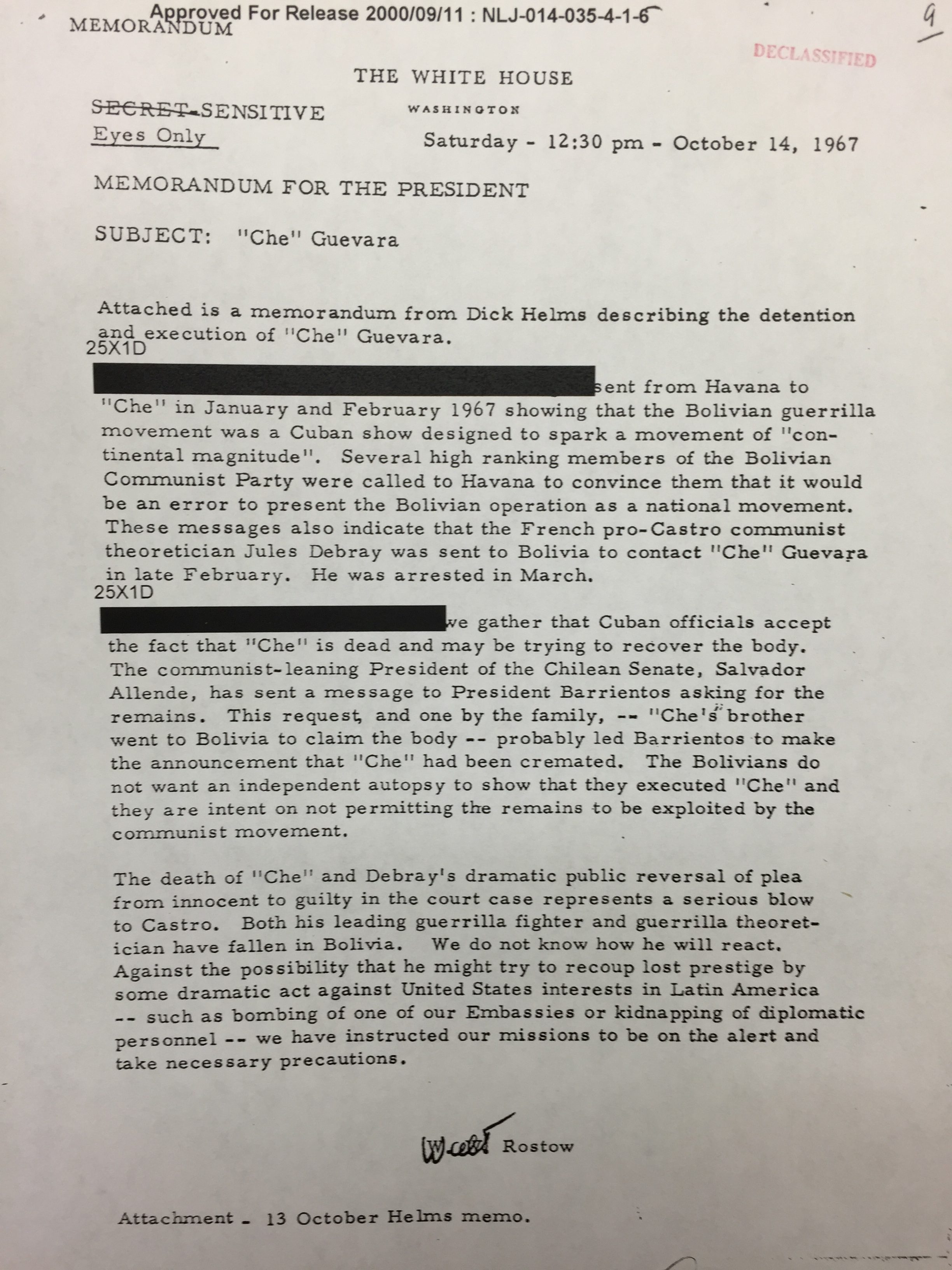

This memorandum—classified SECRET-SENSITIVE/Eyes

Only—was prepared for President Lyndon Johnson five days after Che’s

death. It transmitted a short summary from CIA director Richard Helms

confirming the details of Che’s final hours. Helms’s attached report,

“Capture and Execution of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara,” confirmed that Guevara

had not died from “battle wounds” during a clash with the Bolivian

army, as the press had reported from Bolivia, but rather had been

executed “at 1315 hours…with a burst of fire from an M-2 automatic

rifle.”

The White House memo also confirmed that the Bolivian

government was covering up its role in Che’s execution by claiming his

body had been cremated and could not be repatriated to his homeland of

Argentina, or to Cuba. Che’s brother, Roberto, had traveled to Bolivia

to ask that his corpse be turned over to the family; the socialist

senator from Chile Salvador Allende had formally requested that the body

be turned over to Chile, which Washington interpreted as an effort by

Fidel Castro to recover Che’s remains. “The Bolivians do not want an

independent autopsy to show that they executed ‘Che’ and they are intent

on not permitting the remains to be exploited by the communist

movement,” President Johnson was informed.

Guevara’s death “represents a serious blow to Castro,”

according to the report to President Johnson. The CIA had intercepted

clandestine messages from Havana to Bolivia that revealed that Fidel had

intended the insurrection in Bolivia to be “a Cuban show designed to

spark a movement of ‘continental magnitude.’” Castro had even summoned

ranking members of the Bolivian Communist Party to Havana to advise them

not to present the insurrection as a nationalist movement, according to

these intercepted messages. Rather, he referred to it as an

“internationalist movement.” “The death of Guevara carries these significant

implications,” White House aide Walt Rostow reported to Johnson in a

separate memo to reinforce this point.

- It marks the passing of another of the aggressive, romantic revolutionaries like Sukarno, Nkrumah, Ben Bella—and reinforces this trend.

- In the Latin American context, it will have a strong impact in discouraging would-be guerrillas.

- It shows the soundness of our ‘preventative medicine’ assistance to countries facing incipient insurgency—it was the Bolivian 2nd Ranger Battalion, trained by our Green Berets from June-September of this year, that cornered [Guevara] and got him.

How would Fidel react? US officials worried that “he might

try to recoup lost prestige” by undertaking a dramatic act against the

United States—“such as bombing one of our Embassies or kidnapping of

diplomatic personnel.” The State Department sent a precautionary

security alert to US ambassadors in the region.

The Cuban revolution, however, was not known to engage

in international terrorism; no bombs were detonated at US embassies and

no diplomats were targeted. Fidel’s initial reaction was to give a

fiery, solemn, and poignant speech during a memorial rally for Guevara

on October 18, speaking directly to some of the points raised in the

classified reports circulating at the highest levels of the US

government.

Che’s death, Fidel declared, was “a hard blow, a

tremendous blow for the revolutionary movement.” But, he added, “those

who boast of victory are mistaken. They are mistaken when they think

that his death is the end of his ideas, the end of his tactics, the end

of his guerrilla concepts, the end of his theory.”

Insurgencies continued, as did US-led counterinsurgency

operations, particularly in Central American countries like Guatemala,

El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Indeed, with Cuban logistical and training

support, within a decade of Che’s execution the Sandinista National

Liberation Front had become a formidable movement and would eventually

overthrow the Somoza dynasty. Officials in Washington were mistaken if

they believed Guevara’s ideas, concepts, and committed resistance would

be buried along with his body. His failed guerrilla-warfare tactics may

not have been inspirational, but his martyrdom at the hands of the CIA

certainly came to be.

In

Cuba, the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Che’s death

underscored a continuing effort to energize the revolution and its

commitment to stand up to the United States. At a rally in Santa Clara,

where Guevara is buried, Cuban Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel quoted

the revolutionary’s admonition that “imperialism can never be trusted,

not even a tiny bit, never.” In the face of Trump’s bullying rhetoric

and punitive policies against Cuba, Díaz-Canel reiterated that “Cuba

will not make concessions to its sovereignty and independence, nor

negotiate its principles.”

The fate of Gustavo Villoldo’s memorabilia also

illustrates Guevara’s iconic and romanticized legacy. Villoldo

eventually decided to auction off his scrapbook on the execution of Che;

the auction was conducted on October 25, 2007, by Heritage Auction

Galleries of Dallas.

Initially, the minimum required bid was $50,000. But after

the auction company received an inquiry of interest from the government

of the late Hugo Chávez in Venezuela—Chávez presumably intended to

acquire the hair and return it to Che’s family in Santa Clara, Cuba—the

minimum bid was doubled to $100,000. When the scrapbook went on the

auction block, however, there was only one bidder—a Texas bookstore

owner named Bill Butler, who agreed to pay the $100,000 plus a $19,500

sales commission.

Butler said he intended to display the binder in his Houston bookstore. He had made this unique and expensive purchase, he told reporters, because Che Guevara was “one of the greatest revolutionaries in the 20th century.”

Butler said he intended to display the binder in his Houston bookstore. He had made this unique and expensive purchase, he told reporters, because Che Guevara was “one of the greatest revolutionaries in the 20th century.”

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar